This article was originally published on The Grow Network.

Walking out into the forests or fields and coming back with an armload of food and medicine is a rewarding experience. With every new plant that you learn to identify and use, you become more empowered to care for yourself and your family. You also become less dependent on—and less vulnerable to—big, corporate entities. But this expanding freedom also comes with the responsibility of ensuring you forage safely.

Poisonous plants exist. Some of them look like good plants. Some plants are good or bad, depending on the quantity. And even the safest plants can harm if harvested from a contaminated environment.

I want to help you maximize your rewards while minimizing your risks. That’s why I am presenting you with 15 rules for safe wildcrafting. The more experienced you become, the more you’ll see exceptions to the rules and know when to ignore them. But I advise the novice to follow them all, because nobody wants to become a cautionary tale.

1) Go Slowly When Foraging

The No. 1 rule with any new plant is to go slowly. You can have allergies and intolerances to wild plants, just like you can to conventional foods. The first couple of times you sample a plant, use a small portion. Also, you should only try one new plant at a time. This way, if you have a reaction, you’ll know which plant caused it.

2) Talk to a Local Expert

Local experts will often know little tips and tricks that the books and websites won’t mention, and they will have specific knowledge about how the plants look and behave in your area.

If you can’t find an expert in your area, books and websites are an acceptable way to learn wildcrafting. However, they can’t warn you if you’re about to make a mistake. Use caution and consult multiple sources to minimize your risks.

3) Don’t Eat a Plant Just Because Someone Said It Was Okay

I really hope this one goes without saying. If you watch someone harvest it, prepare it, and eat it—and if they’re still alive the next day—then maybe you could try a little.

4) Know Your Environment

Physical hazards include thorns, holes, ledges, wild animals, moving vehicles, quicksand, and volcanoes. Just keep your eyes open and don’t stick your hands and feet anywhere you won’t be able to see them.

Chemical hazards can be a bit trickier to detect. Don’t wildcraft from locations that get sprayed with herbicides or pesticides. (If you don’t know, ask. You don’t want to eat that stuff.)

Avoid foraging beside busy roads. When it rains, the ditches are irrigated by vehicle-waste runoff. Many municipalities will also spray herbicides along the sides of rural roads. Apparently, this saves money compared to running the mowing trucks. But it also ruins many lightly trafficked areas that I would otherwise love to forage from. Areas around trash storage, treated wood, and industrial waste should also be avoided.

Only harvest plants from pure waterways. Streams and rivers can carry dangerous waste for miles.

Respect private property. Don’t go foraging around someone’s house after dark. Getting mistaken for a burglar and shot would just ruin your evening. And why were you foraging in the dark, anyway?

Lastly … you know what poison ivy and poison oak look like, right?

5) Use All of Your Senses While Foraging

How does the plant look? What patterns do you see? What colors? What’s the overall shape? How does it feel? (Rough? Smooth? Fuzzy?) What does it smell and taste like? (Ideally, you would be reasonably sure it wasn’t poisonous before tasting it or even touching it.) Does it have a peculiar sound? Yes, plants can have telltale sounds.

6) If a Plant Doesn’t Match, Don’t Use It

Sometimes you’ll come across a plant that looks ALMOST right, but something doesn’t quite fit. You may have found a subspecies or variation. Then again, it might be a dangerous look-alike. It’s best just to leave that one alone until you can get a firmer identification.

7) Avoid Plants With White Sap

This one has a number of exceptions. Some plants, like dandelions, are perfectly safe. Others might be safe once they’ve been correctly prepared. But as a general rule, if a plant has white sap, leave it alone.

8) Avoid Plants With White Berries

This rule has almost no exceptions. Plants with white berries are plants that do not mess around. Don’t even touch them.

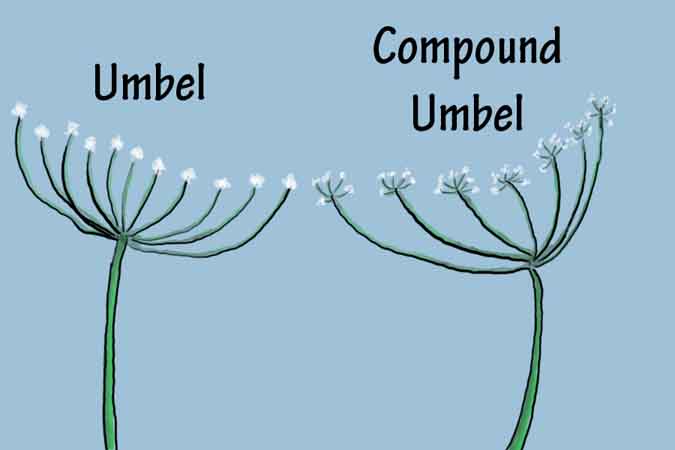

9) Be Humble With Umbels

If you see a plant with umbels,1) you’d better be 110% sure of what it is before you harvest and use it. Elderberry, yarrow, and carrots all form umbels, and they’re great. Poison hemlock has umbels, too, and it will render you in the permanent past tense.

Unfortunately, a lot of these plants will look very similar. I’m not saying that you shouldn’t ever wildcraft them, but you should probably build up your skills on safer plants first. When you’re ready for the umbels, double-check their characteristics every single time.

No matter how smart you are or how much experience you have, anyone can poison themselves if they get cocky or careless. Do yourself a favor and be humble with the umbles.

10) Be 115% Sure About Mushrooms

Mushrooms take the term “poisonous” as a personal challenge. Some of them, like the death cap mushroom, reportedly taste good. To make things worse, mushroom look-alikes can be very tricky to tell apart.

On the flipside, mushrooms are delicious and a lot of fun. They can be wildcrafted safely if you choose the right type. Some mushrooms, like morels and puffballs, are reasonably safe for beginners to gather. Just exercise caution, research their appearance and look-alikes, and go out with an experienced guide until you get the feel for it.

11) If It Looks Like an Onion AND Smells Like an Onion, It’s an Onion

This rule works for garlic too, but the plant you find has to both look and smell oniony or garlicky. There are some dangerous look-alikes, but none of them are also “smell-alikes.”

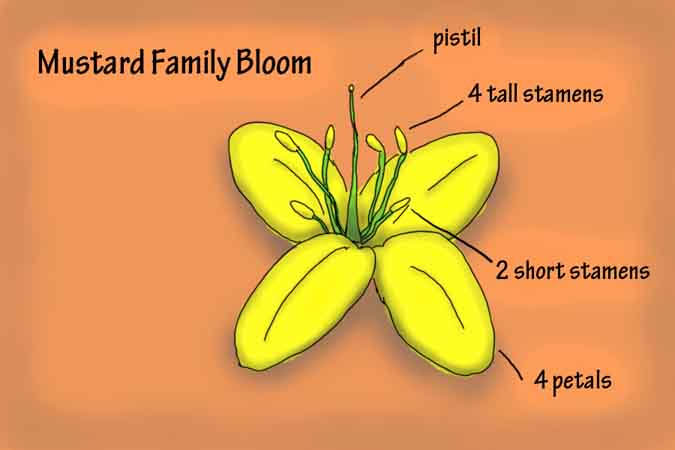

12) All Mustards Are Edible

You can find mustards (Brassicaceae family) all over the world, and they’re all edible. Great. So what does mustard look like? The surest way to identify them is by the bloom. All mustard family plants have 4 petals and 6 stamens2) (4 tall and 2 short). The flowers are often small, so you may need a magnifying lens. Some members of this family may be too spicy to eat in any quantity.

Read More: “Mustard Greens: What You Need to Know Before You Grow (With Recipe)”

13) If It Looks Like a Mint AND Smells Like a Mint, It’s an Edible Mint

Mints (Lamiaceae family) usually have square stems and opposite3) leaves. These leaf pairs will rotate back and forth 90 degrees as they move up the stem. If a plant looks like a mint but doesn’t smell minty, avoid it. It might be fine. It might not.

14) Seeing an Animal Eat It Does Not Make It Safe

Animals can eat a lot of things that would make us sick or dead. They usually know what’s good for them. They don’t know what’s good for us. Don’t copy the animals.

15) Experience Trumps Theory

It may be very helpful to watch a video or read a book about wildcrafting. But until you’ve actually gone out to harvest and use a plant yourself, you can’t rely on that skill. Issues will often come up that books and videos can’t prepare you for. Theory is great for laying a foundation of knowledge, but experience is the ultimate teacher.

Whether the grid goes down or you just have a kid with a tummy ache, do you want to know that you’ve read about it in a book or that you’ve successfully harvested and used these plants before?

Conclusion

Hopefully, this guide has encouraged you, rather than scaring you off. Wildcrafting is a wonderful way to empower yourself, and it’s just a really fun way to spend an afternoon. If you follow the rules and use a bit of common sense, you’ll come back in one piece.

What are your favorite plants to wildcraft? Do you have any tips that I missed? Let me know in the comments, and we can get a good plant talk going.

Read more from the Homestead Guru: Falling Fruit, A Global Map to Help You Get Your Wild Forage On